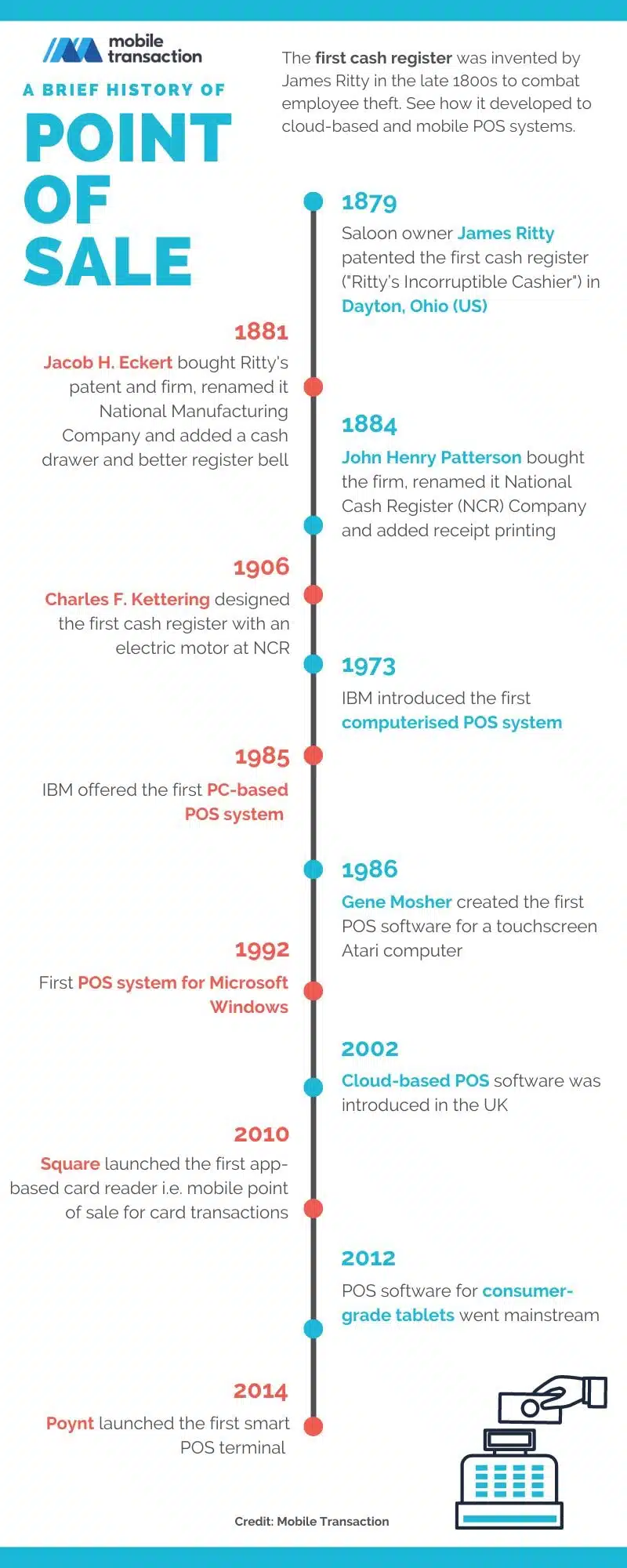

Imagine your shop without a point of sale or any reliable means of tracking the day’s sales. This was the reality of many shop owners before the 1880s. Traders had little insight into their transactions or income, and it was relatively easy for staff to steal from the takings.

This changed when an unknown saloon owner from Ohio got an idea that would change business forever. Let’s go back to the beginning for a detailed history of POS (point of sale).

The story behind the first cash register

After the American Civil War in the late 1880s, many American businesses grew and had to hire strangers to assist customers. It was very easy for these hires to pocket the money given by customers as there was no way to monitor sales, so internal theft was rife in bars and shops.

This changed when the saloon owner James Ritty from Dayton, Ohio, invented the first mechanical cash register. His bar, The Pony House, was well visited. Unfortunately, he also had dishonest bar staff pocketing the bar’s earnings. Being fed up with this, Ritty finally found the solution on a steamship journey to Europe.

On the steamer, he became fascinated by a mechanism that counted how many times the propeller revolved. He started considering whether something similar could be used to register payments at The Pony House.

Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier, the first cash register model ever made. Photo: National Museum of American History

As soon as he arrived home in Dayton, James Ritty and his brother John worked on this concept. It led to the development of a device that became the prototype of the first cash register ever. In 1879, the design was patented as “Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier”.

A big display showed the sums paid by customers, while an internal compartment tallied total receipts, but there was no receipt printer or cash drawer. Ritty founded a small factory to produce this new mechanical cash register, but reportedly only sold one: to John Henry Patterson who owned a coal shop in Coalton, Ohio.

Early developments of the little-known cash register

Overwhelmed with the responsibility of running two businesses – and preferring saloon life – Ritty sold the company to Jacob H. Eckert who renamed it National Manufacturing Company in 1881. Eckert thought the cash register needed more features to be successful, so he added a cash drawer and tweaked the bell that rang the sales in.

It was the seller’s responsibility to enter all transactions on the till, and when he or she pressed the ‘Total’ button, the till drawer opened and a bell chimed.

It is said that this was when the tradition of ‘just-below prices’ (odd prices like $0.99 or £2.98) started. Because the registration of a sale happened in connection with an exchange of cash, the prices ended with 99 cents so the employee had to open the cash drawer to exchange coins. The bell thereby chimed and the boss was alerted that there was a sale, making it more risky to steal cash.

Still, the cash registers were largely unknown and difficult to sell, so Eckert sold the firm to John H. Patterson in 1884. Patterson changed its name to National Cash Register Company (known as NCR Corporation from 1974 and still a large company).

An 1880s model by National Cash Register Company. Photo: NCR Corporation

To prevent fraud, Patterson added a paper roll to print receipts for each transaction: one for internal bookkeeping and recording all transactions, and another for the customer’s bookkeeping. The world’s first aggressive sales team was created at NCR to sell the optimised cash registers, and finally, the point of sale was popularised in shops.

From mechanical to electronic tills

The early cash registers were completely mechanical. In 1906, NCR inventor Charles F. Kettering created the first cash register with an electric motor. During the early 20th century, many other cash registers followed suit with electric motors, but otherwise, there was little innovation for decades.

When electronic calculators arrived on the market in the 1950s and 1960s, it wasn’t long until tills became completely electronic too. From the 1970s, electronic cash registers finally dominated the market.

The first point of sale (POS) system was developed by IBM in 1973. These were big machines that could control up to 128 tills. Even though it had limited features, the POS system was pioneering at the time because it represented the first commercial use of multiple new technologies such as the local area network (LAN). One of the first tills that used microprocessors was developed for McDonald’s in 1974.

Gene Mosher with his pioneering point of sale software for a touchscreen interface. Photo: GeneMosher, Wikimedia Commons

During the 1980s, data machines with graphical interfaces had been developed, which didn’t take up too much room and did not cost a fortune.

Consequently, the first PC-based POS system was launched by IBM in 1985. This was followed by Gene Mosher’s first point of sale software for a graphic touchscreen interface in 1986. He developed colourful buttons for different menu items (it was for a deli) to tap on, and several of his interface elements, such as back/forward buttons and tabs, were later adopted by internet browsers.

After the internet took off in the early 1990s, POS systems for Microsoft Windows were developed. In the years that followed, hundreds of providers on the market created and offered computerised POS systems. These could be used on all sorts of machines and operating systems, but Windows was the leading one.

Cloud-based POS systems

The traditional, computerised POS systems in the 1990s and noughties required its owner to install, maintain and update both hardware and software. The term EPOS (electronic point of sale) became more familiar in retail environments.

The internet and the development of cloud-based systems have since made it possible to offer EPOS in the form of Software as a Service (SaaS). This is where the software is owned and run by a service provider, and the user pays a monthly or annual fee for the use of this product.

Since the introduction of cloud-based POS systems in the UK in 2002, many of the systems were used on industry-grade touchscreen PCs.

Around the time when tablets and smartphones became mainstream (iPhone was released in 2007 and iPad in 2010) a new app-based card reader was launched in 2010 by Squareup in the US. This was called Square Reader and enabled merchants to use their smartphone as a mobile point of sale accepting card payments with the attached credit card swiper.

A couple of years on, many cloud POS systems were compatible with consumer-grade mobile devices including iPad and Android tablets. The mobility and flexibility of these systems were part of a general trend to make business tools more accessible to micro-merchants. Smartphones got smarter, card machines more affordable, and POS systems less intimidating with the easy software setup.

Great advantages of cloud-based tills are that users have access to the system any time and anywhere, and that data and functions are backed up, maintained and updated by the software provider. And the better the analytical data is, the better business decisions you can make on the spot.

The growth of customer loyalty programmes and different ways to accept cards expanded the range of features required on tills. Consequently, today’s POS systems do not only manage sales, but also a number of important functions related to marketing, pricing, inventory management, customer service and so on.

Cloud-based systems are now dominating the market, compared with the so-called legacy POS systems installed on your local hard drive.

Mobile POS terminals and merging of sales channels

The popularity of smartphones and tablets has made mobile terminals attractive among small businesses, either as the primary point of sale or to supplement a stationary system. In its purest form, this could be a card reader connected to a phone or tablet by cable or Bluetooth, controlled by an app on the mobile device.

It could also be a portable ‘smart POS terminal’ acting as an all-in-one touchscreen checkout and card machine in one device. Poynt launched the first of this kind in 2014, and other card terminal providers like PAX and Verifone followed suit. Such portable POS systems rely on the customer paying by card, as otherwise cash management gets complicated.

Poynt Smart Terminals are standalone touchscreen checkouts that can accept cards. Photo: Poynt

With the boom of ecommerce, Click & Collect and online payments during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 until now, the point of sale has relied more than ever on the integration between in-person and online sales. Businesses unprepared to adapt have suffered losses, with POS providers suffering a hit – at least temporarily.

But as long as people are still paying for things face to face – by cash or a physical card – the POS system remains an integral part of retail and hospitality.