The electronic card machine, also called PDQ or EFTPOS terminal in industry jargon, is one of the most commonly used electronics in everyday life – like our mobile phones and computers.

But do you ever think about the origin of this ingenious device that pays for our essentials without money in sight? When did card machines come out? We have reviewed the history of card terminals, developments over time and future outlook.

The invention of the credit card

Above all, the invention of the card terminal owes itself to the widespread use of credit cards as a means of payment.

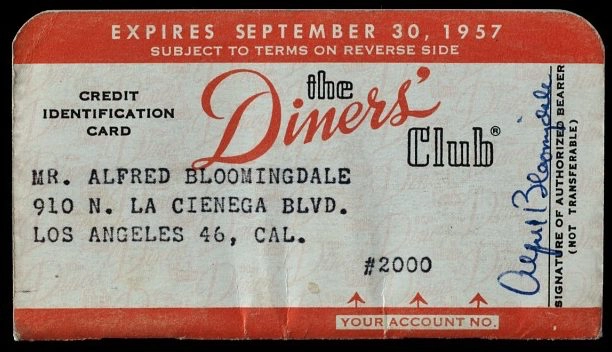

The first payment card, Diners Club, appeared in the United States in 1950, followed by American Express in 1958. These were both charge cards, where you pay the full amount on credit at the end of each month, but they were called credit cards at the time.

The main idea? To give merchants a standardised way to settle transactions with their own and the customer’s bank, without the use of cash.

1957 Diners Club credit card. Photo: Smithsonian Institution

In 1958, Bank of America released the first bank card, called BankAmericard (renamed as Visa in 1976). This was the first to work on a revolving credit system where the monthly balance is carried over to following months for a fee.

The first payment card in the UK was the charge card American Express, released in 1963. On 29th of June 1966, Barclays followed BankAmericard’s footsteps and issued the first all-purpose credit card in the UK. The original UK debit card was released two decades later in 1987, also by Barclays and called Visa Delta by the Connect brand.

First card machine: the credit card imprinter

The first payment cards were in cardboard and thus required lots of manual recording at the point of sale, but American Express revolutionised this with the first plastic credit card in 1959. The cardholder’s name, address and unique identification number were marked in embossed lettering on these cards.

This enabled merchants to produce an imprint on carbon paper slips intended for the bank, merchant and customer as proof of purchase. The imprint was done on the first non-electronic card machine: the credit card imprinting machine – also called credit card imprinter, sometimes referred to as a “click-clack” machine due to the sound it makes when you impress the carbon paper.

Early credit card imprinter from circa 1960. Photo: Smithsonian Institution

The device allowed merchants to record credit card transactions quickly, as opposed to manually writing information written on a flat paper credit card. The carbon paper slips were signed by the customer, one of which was sent to the bank to process the transaction, another for the merchant to keep and the last as a receipt for the customer.

The development of this device was a big leap from time-consuming, manual handwriting to automatic printing of card information. Today, some shops are still using a flatbed credit card imprinter as a backup method for manually recording a card when the chip and PIN machine is down.

Arrival of the first electronic card machine

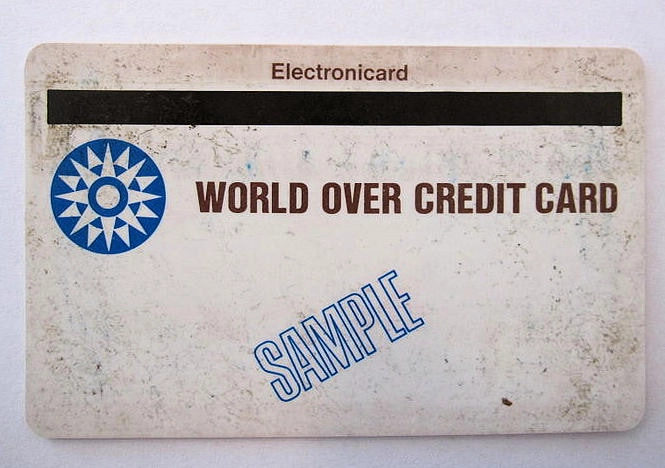

In 1970, a magnetic stripe was added to payment cards and the card payment system thus became electronic.

Magnetic stripe card with the IBM 360 logo. Photo: Wikipedia

The magnetic stripe was invented by an IBM engineer and made feasible thanks to IBM 360, a system that allowed the independent configuration of external peripherals such as hardware and printers.

The magnetic stripe contained information needed to validate the payment: name of the cardholder, card number, authorisation code and expiry date of the card.

The first electronic payment terminals were created to read these magstripe cards. The technology made it possible to conduct increasingly secure transactions, control the account balance of the customer, and accept or refuse a transaction on the spot.

In 1973, the first electronic transaction authorisation system was created in the United States, linking merchants to the Visa data centre in California.

It was, however, necessary to wait for the 1980s to see the spread of the electronic payment terminal connected to the Visa and Mastercard networks.

With the magnetic stripe system, the transaction was already electronic. However, signing to authorise a receipt issued by the merchant was still a requirement at the end of the transaction after the card was inserted in the terminal.

The chip, a French invention

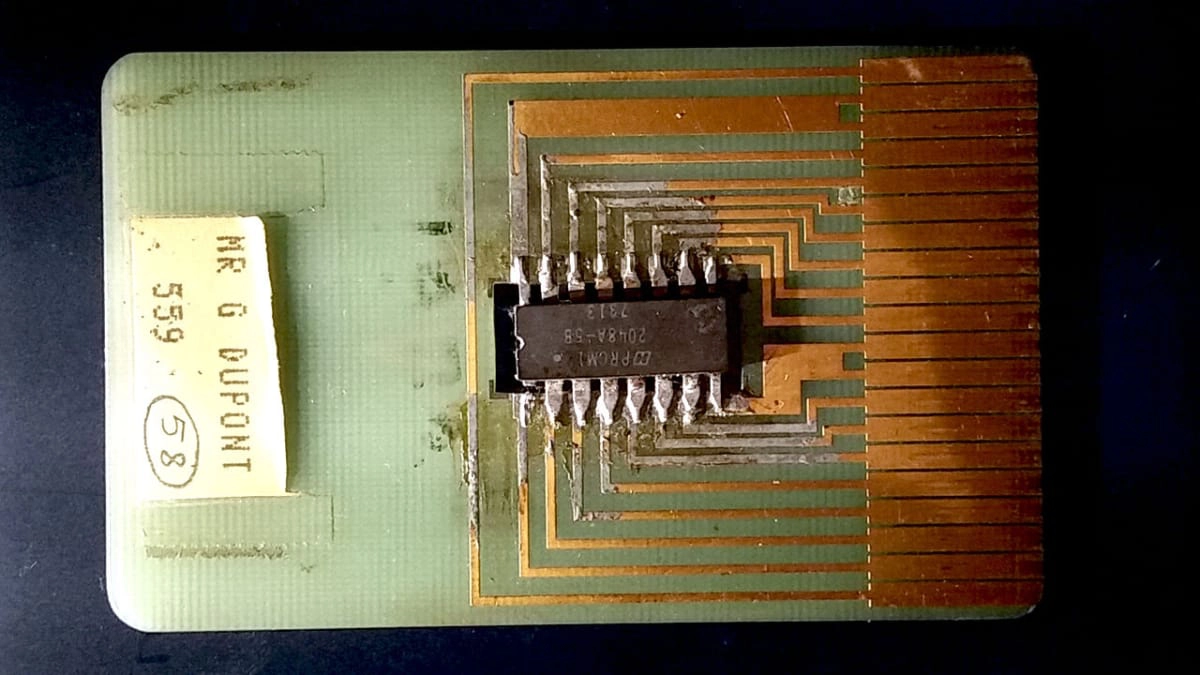

In 1975, the French inventor Roland Moreno patented the chip card, also referred to as the smart card.

Used for the first time in calling cards, this revolutionary microprocessor became widely used on bank cards in 1985. Its implementation on all debit cards first became mandatory in France from 1992.

In the UK, it wasn’t until 2004 that chip and PIN cards were introduced, and they were made mandatory on all British payment cards from February 2006. The adoption of the four-digit PIN system connected to the chip decreased fraud significantly. Pre-2004, customers had to authenticate transactions with an easily-replicable signature.

Prototype of the chip card by Roland Moreno (1975). Photo: Wikipedia

The chip card is capable of storing a large amount of information and communicating in real time with the customer’s bank to validate or invalidate the authorisation of the transaction.

It also offers much greater security than the magnetic stripe card system, which could easily be cloned.

However, it was necessary to wait until 2015 for this system to reach the United States.

The first electronic card terminals

It wasn’t until 1967 that the first automatic teller machine (ATM) was launched by Barclays in the UK – the first electronic machine for cards in the world. To withdraw cash, customers had to enter a 4-digit PIN connected to their card – the first card PINs in existence.

At this point, shops were still using manual credit card imprinters and verification by customer signature to process credit cards in shops, which was a lengthy process. In 1973, National BankAmericard launched the first electronic authorisation, clearing and settlement system, which laid the foundation for all electronic card processing onward, but still required a 5-minute phone call per authorisation.

The invention of swipe cards in 1970 did not actually change the way shops accepted cards until the first bulky, electronic card machine was launched by Visa in 1979. This was also the year when MasterCharge (competing since 1966) became MasterCard, and credit cards were replaced to include a magnetic stripe.

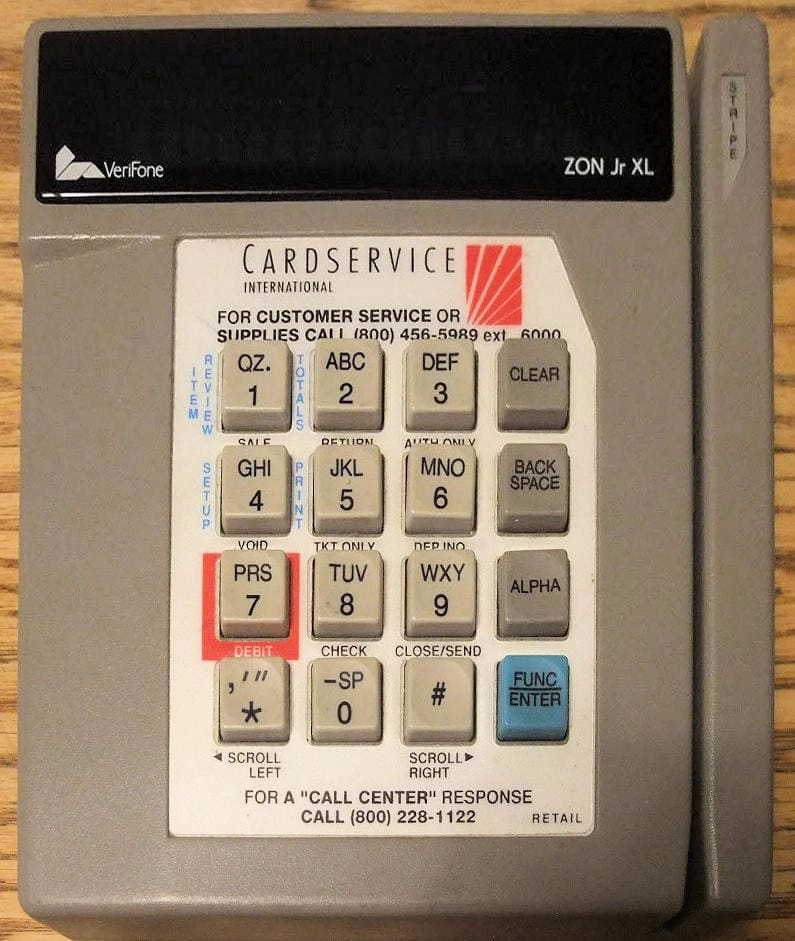

ZON Jr XL (1984), the first Verifone terminal with authorisation check. Photo: Joe’s Blog

The introduction of the electronic card machine greatly reduced card processing times, compared to manual imprints and phone authorisations. In 1982, Hawaiian company Verifone released their first POS terminal for cards, and their 1983 ZON model became the benchmark for modern card terminals.

Stationary terminals: connection options

The first solution implemented to transmit information between the electronic payment terminal and customer bank was based on a landline connection, also called PSTN (public switched telephone network).

For this to work, the card machine had to be fixed and installed in one location, connected by cable to the telephone socket.

Ingenico Elite desktop terminal with a connected PIN pad (2006). Photo: Wikipedia

Some card terminals still work through such a phone line, but faster connections are now available. For instance, it is much faster to use the internet than the phone line, since data speeds are constantly increasing.

You can connect today’s terminals to the internet via 3G, 4G, GPRS, WiFi or Ethernet. Terminal providers like Ingenico may make any of these optional so you pay a price based on your chosen connectivity options.

The main thing today is this: all card machines need a connection to the merchant bank to authenticate payments. Whether this connection happens over WiFi, 4G or an old-fashioned landline doesn’t make much of a difference to the transaction.

The wireless terminal

Another technological shift that changed the nature of card transactions is the adoption of mobile phones. With mobile phones, wireless networks became widespread, prompting the development of wireless card machines.

The mobile terminals enables merchants on the go to accept payments by credit or debit card anywhere: in markets, food trucks, during trade shows – wherever there is a compatible network connection.

Depending on the model, mobile card machines can use GPRS, 3G, 4G or slower connections. Transaction data can be sent and received wherever you are, provided you have the network connection a device containing a SIM card.

As early as 1997, Norwegian Telenor Mobile marketed this wireless card terminal. Photo: Norwegian Museum of Technology

These technologies are no longer the preserve of heavyweights like Ingenico and Verifone. Low-cost players such as SumUp and myPOS have in recent years entered the market to allow more entrepreneurs and traders access to flexible card payments.

Portable card machines, on the other hand, use WiFi or Bluetooth. They are not entirely mobile as they can only be used on the fixed premises of the merchant. The term “portable” as opposed to “mobile” is not an official definition, but it is frequently used by terminal resellers.

WiFi terminals were quickly adopted by restaurants to allow customers to pay directly at the table without forcing them to go to the till. Many payment terminals use both WiFi and GPRS/3G technologies and can switch from one to another.

The app-based card reader

Smaller, lighter and cheaper than traditional mobile card machines, mobile card readers have become popular in the UK.

These small devices do not have a SIM card, but are instead connected to a compatible smartphone or tablet running a payment app specific to the card reader. Initially, the card readers were connected via cable with a headphone jack, but nearly all app-based card readers today connect via Bluetooth.

These pocket-sized card readers are particularly suited for e.g. street vendors, mobile merchants with infrequent sales, or for those where buying or renting a traditional card machine is too expensive.

Promo image of the first card reader, Square Reader, launched in 2010. Photo: Smithsonian Institution

Since Squareup’s (i.e. Square’s) first app-based card reader was launched in the US in 2010, fintech companies like iZettle and SumUp have followed suit with their own mobile terminals. The upfront cost is low, and they are often cheaper for low-volume businesses compared to traditional card machines.

Development of contactless payments

In the grander scheme of payments, the emergence of contactless cards was a minor development compared to that of the smart card.

The original technology behind contactless is Near-Field Communication (NFC), derived from radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology used in anti-theft devices. NFC allows information to be transmitted to a device in the vicinity of maximum 10 cm.

In the UK, Barclaycard was the first to adopt NFC in their credit cards in 2007. By December 2014, there were 58 million contactless cards in circulation in the country and 147,000 NFC terminals in use.

NFC cards are accepted on terminals displaying the contactless logo.

Intended for small transaction amounts (the original maximum was £20) by simply waving the card on the terminal, it was first seen as a gadget and often regarded with some suspicion by consumers. This has changed considerably since, with most Brits today using contactless regularly for any amount up to the current £30 limit.

All terminals with NFC capability can also accept mobile wallets like Apple Pay and Google Pay, although less popular mobile wallets may use other contactless technologies like Bluetooth or magnetic secure transmission (MST), which is not built into all contactless terminals.

All new card machines today have contactless functionality, both because of consumer adoption but also because Visa and Mastercard require all card terminals to accept contactless from early 2020.

Terminals are no longer just for card payments

In recent years, a new breed of card machines has entered the market: the smart POS terminals. These are multi-functional devices with touchscreen and third-party apps with features usually offered through POS software.

Poynt was the first to introduce such a device in late 2014. The year after, in October 2015, their Smart Terminal was the first in the world to become a fully certified (PCI-DSS, PCI PTS and EMV certification) smart terminal on the market.

Verifone Carbon 8 is a smart POS terminal with two touchscreens. Photo: Verifone

Other companies such as Clover, Spire Payments, Ingenico and Verifone have since followed suit with tablet-like terminals, some which still feature a physical PIN pad alongside a touchscreen display (e.g. Ingenico Move/5000).

As for chip and PIN, these new smart payment terminals typical require PIN entry on the touchscreen, a PCI-certified technology referred to as PIN on glass.

Biometric card payments and other future trends

In addition to the old PIN or signature system, it is now possible to use biometric data to authenticate the user at the point of payment. One of Ingenico’s latest models, the Move 2500B, for example, is capable of recognising fingerprints. With this system, the user places the index finger on a fingerprint reader integrated on the payment terminal.

This significantly increases the security of the transaction and may even replace the payment card in the future. Payment cards with fingerprint technology embedded on the card are also being trialled by Mastercard.

Mastercard has been trialling fingerprint authentication in the last few years, but it is yet to be popularised. Photo: Mastercard

What will the future of card terminals be in general? Contactless and mobile payments are continuously rising in usage, but the plastic card is still king in the UK – for the first time ever, it overtook cash payments in 2018.

But how it evolves in the next 10 years is still a question mark, given the choice of options on the market. Just consider the smart watches with digital wallet, fingerprint technology, even implants of an NFC microchip… and the fact that people love to buy online, on their phones.

Payments have never been as diverse and fast-developing as now. As for card machines, it’s clear the future takes a liking to touchscreens and wireless devices with way more brains than the first click-clack imprinter.